Lena Henningsen and Damian Mandzunowski to Present at the 'Competing for the People’s Eyes and Ears from Mao to Xi' Symposium, 27-28 June in Prague

15 June 2025

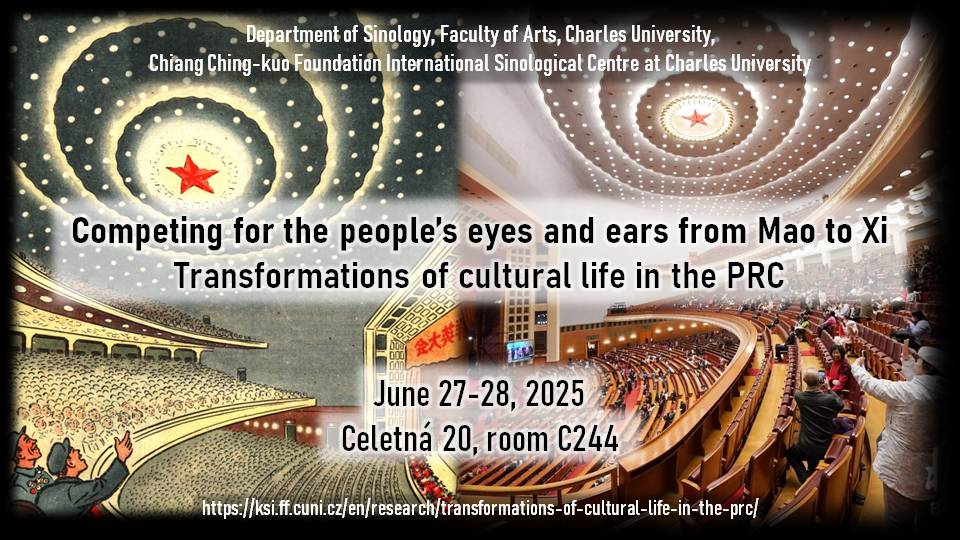

ChinaComx PI, Lena Henningsen, and postdoc researcher, Damian Mandzunowski, are about to participate in an international symposium on transformations of cultural life in the PRC titled Competing for the people’s eyes and ears from Mao to Xi: transformations of cultural life in the PRC to be held at Department of Sinology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University and Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation International Sinological Centre at Charles University on June 27–28, 2025.

In their respective papers, both Lena and Damian will discuss the silences, sounds, and noises of lianhuanhua—albeit in very different ways and to very differing conclusions.

For the conference program, see here, and read on for the two paper abstracts below:

Lena Henningsen (Heidelberg University), “Sounds of Silence: Sonic Comic Stories amid the Noises of Maoist China”

Western comic art has been described as audiovisual. The depiction of noise such as music emanating from a gramophone or of stomping feet, as Eike Exner argues, proved formative for the rise of modern comics in the US. If audiovisual elements are constitutive for the medium of comics, an inquiry into the sonic qualities of lianhuanhua – the pocket size comics genre popular throughout the 20th century – suggests itself; even more so when the context of their consumption, a China immersed in the rumpus of the revolution, is also taken into the account. Throughout the Mao era, lianhuanhua were employed to mobilize readers for the revolution and to instill them with revolutionary fervor, making full use of the text and images in these comics. Often, lianhuanhua told stories of revolutionary heroes and of ferocious fights against the enemies of the revolution. However, I argue that lianhuanhua are much less noisy than their foreign counterparts: speech bubbles exist, but to a lesser extent than in Western comics; sound is not visualized on the panels; pastoral backgrounds to the action often give scenes a notion of peace and quiet; very often, protagonists are depicted solitarily and absorbed in thought, or within small groups and in calm dialogue; even scenes depicting larger groups of people typically do not shout at their readers. Adding to these stylistic inquiries and their changes over time, I will also inquire into the contexts within which comics were read, arguing that this (relative) silence offered readers an escape into an atmosphere of serenity and quietness. This, I contend, added to the popularity of the genre in a Maoist China flooded with the noises of propaganda.

Damian Mandzunowski (Heidelberg University), “Revolutionary Onomatopoeia: Soundscapes in/of Chinese Comics of the Mao Era”

A significant portion of the sonic and visual stimuli capturing people’s attention in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was intermedial. Films often included subtitles indicating how to sing along; radio broadcasts of important editorials encouraged listeners to read along; propaganda posters depicted scenes to be staged and re-enacted. This paper examines another such phenomenon: the depiction of onomatopoeia, interjections, and other expressions of sound in Chinese comics (lianhuanhua) of the Mao era (1949–1976). These popular booklets, enjoyed by millions of children and adults alike, frequently included scenes of evocation, explosions, screams, singing, radio listening, talking, or whispering, but also of natural sounds such as animals chirping or belling and elements like wind, rivers, and forests. Conversely, lianhuanhua functioned as a very “loud” medium: these supposedly silent booklets were often read aloud at street bookstalls or in mobile libraries by groups of children, or by mothers at bedtime. All this was accompanied by the sounds of flipping pages, gasps at plot twists, and the voices of the readers. How did visualised sound relate to image, text, meaning, and reception of lianhuanhua? What changes and continuities in these depictions can be traced over the decades? And which sounds made it into the visual canon of revolutionary onomatopoeia—and which not? This paper offers a first exploration of the intermediality of sound and image in lianhuanhua. By taking a set of exemplary comics as a case study, it explores how popular culture under state socialism drew upon familiar forms while creating indigenous approaches to visualizing soundscapes. It also seeks to enhance our understanding of one of the most influential media in the daily lives of people under state socialism. Expanding beyond the printed form, this paper further highlights lianhuanhua’s cultural significance during a transformative era of modern Chinese history when sound and image converged.