The New Year’s Sacrifice 祝福 (1974) #

Lu Xun 鲁迅 1974: The New Year’s Sacrifice 祝福, illustrated by Yong Xiang 永祥, Hong Ren 洪仁, Yao Qiao 姚巧, translated by Stefanie Gondorf, Lena Henningsen, Charlotte Kräker, Jingying Li, Ghost Tian, Beijing: Beijing renmin meishu chubanshe, 1974.1

Introduction to the text2 #

Lena Henningsen and Ghost Tian

Lost and Gained in Adaptation – Comic Book Adaptation of Lu Xun’s “The New Year’s Sacrifice” (祝福, 1974) #

The 1974 lianhuanhua adaptation of Lu Xun’s (鲁迅, 1881-1936) famous short story “The New Year’s Sacrifice” (祝福, 1924) represents a distinct interpretation of the original. The comic can be seen as a work of art in its own right, yet it is firmly situated in Maoist discourses and in textual practices of the time. In the following, we will briefly sketch this situation, point out how the comic differs from the original as well as from an earlier adaptation. Doing so, we argue that in the process of adaptation the figure of the narrator is lost – yet, through the images, the story also gains.

“The New Year’s Sacrifice”: Lu Xun in Maoist China #

“The New Year’s Sacrifice” relates the story of Xianglin’s wife: It is the story of a poor woman suffering misfortune throughout life. Her misfortune is exacerbated by the social norms of her day. She is poor to begin with, loses two husbands and her young son who is eaten by a wolf. Not only does she have to struggle constantly to make a living, she also suffers as people assume her to have accumulated sin which caused these deaths. The family which employs her even considers her unclean and thus bars her from participating in the spiritual rituals conducted during the Chinese New Year celebrations. Unable to find a way to atone for her assumed sins, Xianglin’s wife loses her mind, her job, her dignity, and, finally, her life.

In this story, Lu Xun clearly blames superstition and old customs for the fate inflicted on the protagonist. However, ambivalence is introduced into the plot as the story is told by a first-person narrator who has returned to his ancestral town after a long time. This narrator chronicles the fate of Xianglin’s wife, but also his own feelings: He feels repulse when confronted with the backwardness of his uncle (Mr. Lu in the story), but he also feels awkward when confronted with the deranged woman whose questions he wants to evade. When, in the end, she dies, it seems not only the townspeople feel a sense of relief (even though the date of her death confirms earlier assumptions by the townspeople that she is inauspicious), but he himself seems relieved, too. Through this figure, the reader of the story is invited not only to condemn old morals and customs, but also to consider his (or her) own position, involvement and accountability for fates like that of Xianglin’s wife.

As such, “The New Year’s Sacrifice” is very much in line with the CCP’s take on ‘superstitious’ and ‘feudal’ practices. The modernist left-wing writer Lu Xun became a central figure in Mao Zedong’s literary policies. In the 1942 Yan’an talks (McDougall 1980; Denton 2016), Mao established Lu Xun as one of the core models for Chinese authors to emulate. Later on, official discourse propagated Lu Xun as a revolutionary, including on propaganda posters from the early to mid 1970s (see, for example the posters collected in the Landsberger collection, i.e. coinciding with the publication of this comic book. Lu Xun’s works continued to be published in the PRC years, with numerous comic adaptations of this stories, and also a wave of internal publications of works by and about Lu Xun setting off in 1972 (Henningsen 2021: 173) when cultural life during the Cultural Revolution began to relax. After the Cultural Revolution, yet and another lianhuanhua version was published, entitled Xianglin’s Wife 祥林嫂 based on movie stills (Lu Xun 1979).

“The New Year’s Sacrifice” in lianhuanhua adaptation(s) #

This is the context which saw the publication of the present The New Year’s Sacrifice comic. Or rather, it saw the remake of a The New Year’s Sacrifice comic, as the artists (Yong Xiang 永祥, Hong Ren 洪仁, Yao Qiao 姚巧) redid their earlier lianhuanhua book in 1974. The present version rests on the adaptation of the text by Xu Gan 徐淦 from 1957 with only minor changes. The images, however, are entirely redrawn in different style. Two aspects are particularly noteworthy, both of them resulting in a reduction of complexity of the lianhuanhua versions vis-à-vis the original short story. One is a reduction in complexity of the plot as the first-person narrator of the story is lost in adaptation – the other a stylistic reduction of the complexity of emotions that result from the style of the text and the accompanying images.

Only in rare instances does the text of the lianhuanhua reveal the emotions the characters experience – mostly in Mrs. Lu’s reactions to her husband. The sentences accompanying the panels bring forward the action of the story, they record the dialogues between the characters. Through their actions and words, they come to life and display their different personalities. The panels add to this, they show emotional expressions on the faces of the characters and they show differences in power among the characters by how they interact with each other. So while the narratorial voice with its ambivalence and its feeling of discomfort towards the backwardness of the situation and towards Xianglin’s wife have disappeared from the text, the images transmit this atmosphere. A particular strong effect is created as the tranquility and beauty of the setting in a Jiangnan town is depicted in water color panels. It forms a stark contrast to an utterly cruel story. Scenes in which Xianglin’s wife suffers harshly – such as pages 17-21 when she is remarried against her will or the penultimate page of the lianhuanhua – are rendered in darker shades.

In addition, the plot of first-person narrator of the original story is purged from the plot. Instead, the story is told by an omniscient narrator who remains outside the plot. The events are related in chronological order of Xianglin’s wife’s life – and not in the order in which the first-person-narrator experiences his return to the small town and learns about the miserable fate of Xianglin’s wife. While in the lianhuanhua her death in the snow by the river is related in the last page (the text describing how the village is celebrating the New Year – the image depicting her lying dead and motionless in the snow), in the original short story, this inauspicious (yet relieving) death prompts the narrator to find out about her life and retell the life of Xianglin’s wife. This loss of the narrator distinctly reduces the ambiguity in the original plot.

In the original text, in candidly revealing through inner thoughts his complacent attitude towards the circumstances of Xianglin’s wife, the narrator figure serves the primary function of highlighting the amoral and uncaring nature of Chinese society as Lu Xun perceived it. When the narrator has difficulty answering Xianglin’s wife’s questions regarding afterlife, he begins to feel “deeply unsettled” and wonders whether he had “made things worse for her” by his reply (Lu 2009: 164); it seems, at first, that the narrator is concerned with the woman’s well-being. However, readers are quickly disabused of this notion as he “laughed at [him]self”, deciding that he was “perfectly insured with that last ‘I don’t know’” and that “if something did now happen, it could have nothing to do with me” (Lu 2009: 164). Here, it becomes painfully obvious that the narrator cares nothing for Xianglin’s wife but worries only about his own culpability in the event of a problem. When he is later told of her death, his thoughts likewise demonstrate his coldly indifferent response; he remarks in relief, “I realized the thing I had dreaded was now past; that I no longer needed to dwell obsessively on the business, on my ‘I don’t really know’ … I became steadily easier in my mind” (Lu 2009: 165). Notably, this is the sentiment that immediately prefaces the readers’ introduction to the life story of Xianglin’s wife, while the tale is concluded by the narrator waking from a nap to the sounds of New Year’s celebrations. At this point, he “accepted its comfortable, torpid embrace, letting the New Year’s Sacrifice cleanse me of the doubts and misgivings that had troubled me all day” (Lu 2009: 177). For the narrator, the whole of Xianglin’s wife’s tragic life and immeasurable suffering amounted to little more than a day of troubled thoughts, easily cleared by a nap and a lethargic welcoming of the New Year. By enveloping the story of Xianglin’s wife in the apathetic outlook of this outside narrator, Lu Xun presents a disturbing and biting criticism of the callousness exhibited by society’s privileged and borne by its poor.

Lacking this narrative framework of the uncaring spectator and centering only on the experiences of Xianglin’s wife, the lianhuanhua adaptation presents a simplistically sympathetic story which does not achieve the critical complexity of the original text. Unlike the original where two central characters—the first-person narrator and Xianglin’s wife—blur the standard distinction between protagonist and antagonistic forces, the lianhuanhua is told from the removed point of view of an omniscient narrator with Xianglin’s wife acting as a clear protagonist. The comic’s text focuses on event description rather than psychological explication as in the original, and its images likewise are drawn in a realistic style with little depiction of emotional or mental states; readers are thus provided a straightforward telling of plot with no imposition of external analysis. In this way, the lianhuanhua is akin to a blank slate onto which readers may project their own understandings and feelings without the influence of a given narrational perspective. Because readers are likely to sympathize with the protagonist of a story, the foremost emotional takeaway from the lianhuanhua adaptation becomes one of simple compassion or pity rather than the disquiet aroused when asked to embody in the first-person an indifferent narrator placed in opposition to a suffering protagonist. This unsophisticated call to sympathy is an easy task for readers to fulfill, especially for a tragic character such as Xianglin’s wife, and does not invite the critical reflection on societal apathy that is fundamental to Lu Xun’s original short story.

“The New Year’s Sacrifice”: Continuity and change from 1957 to 1974 #

The 1957 (republished in 1963 and reprinted again in 2005) and 1974 versions have only minor changes in the texts below the panels. Only page 55 sees a larger change, with the merging of two pages into one in the 1974 version (pages 55+56 in the 1957 version are merged into one page in 1974). The images accompanying the text are similar in that often the persons are displayed in similar arrangements, though, often from different angles. The style of the images, nonetheless, is very different. While the 1974 version is drawn in watercolors, the earlier version is black and white drawings which allow and call for more simplification in style.

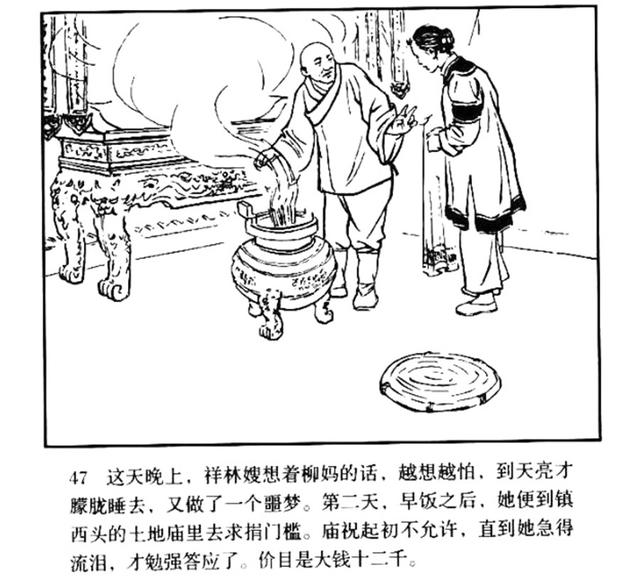

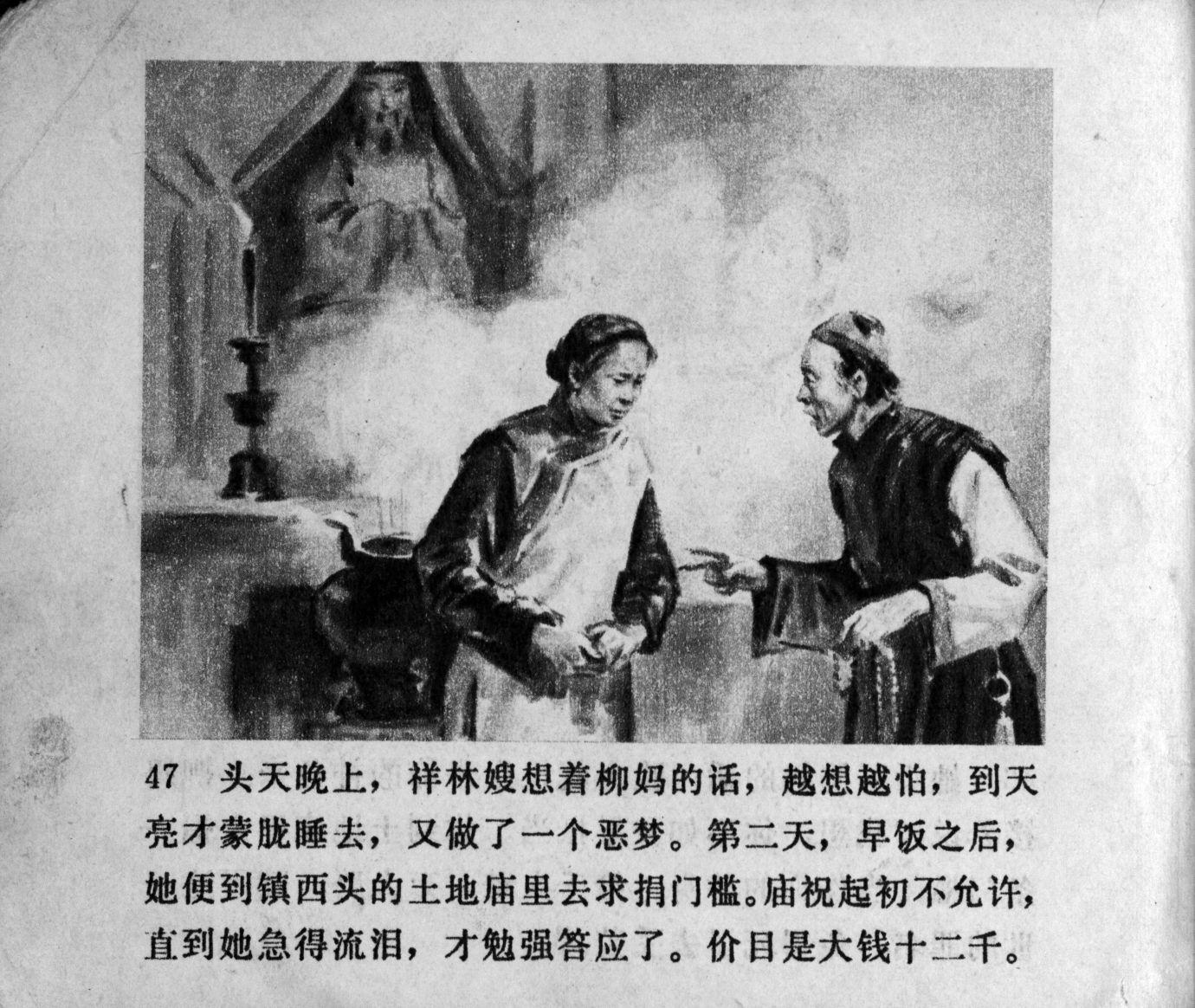

Two figures, nonetheless differ among the two versions: the temple attendant and the literate person appearing towards the end of the comic. As to the former, his clothes and bold head clearly identify the 1957 temple attendant as a Buddhist monk, while his 1974 counterpart is less clearly identifiable (page 47).

Page 47

This might have to do with the fact that during the Cultural Revolution Buddhism had been one of the objects of criticism.

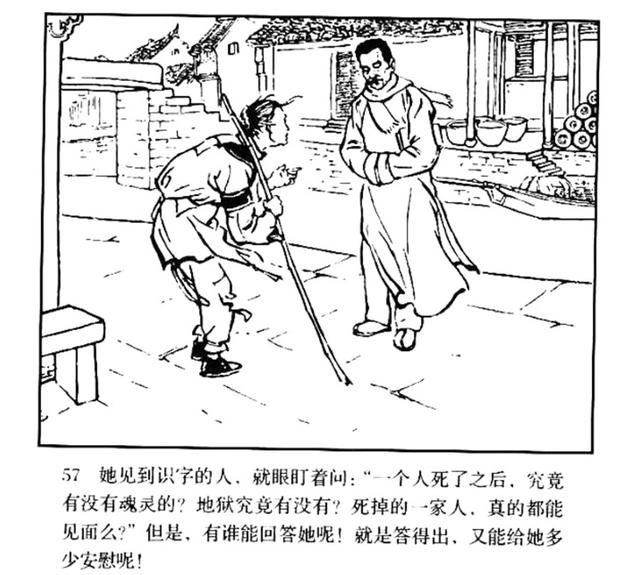

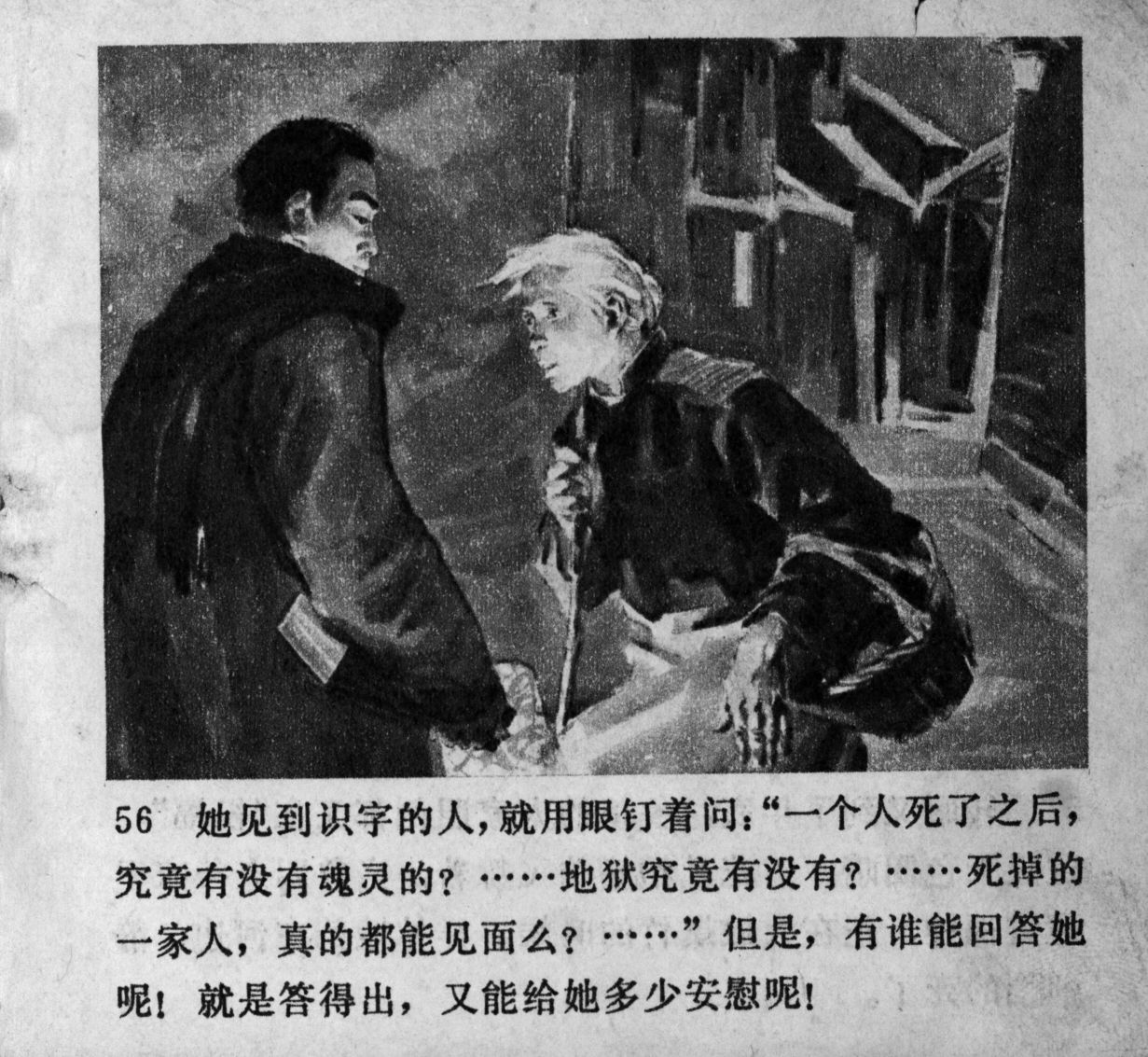

On the penultimate page, Xianglin’s wife inquires with a literate person about life after death. In both images, she is depicted as a beggar, in a crouching pose. What differs, however, are the perspective and the looks of the anonymous literate person. In 1974 (page 56), Xianglin’s wife is in the center of the panel, her white face and hair radiating in front of the dark background, the literate person with whom she inquires is depicted at the left-hand corner of the page, only displaying half of his face. He has short hair, wears a dark coat and has what may be a book under his arm. In the 1957 version (page 57), however, the literate person bears the markers of an early 20th century intellectual more clearly: his hair is short, he has a moustache, he wears a scarf and a simple gown and uses its sleeves to keep his hands warm. He also has a book tucked under his arm. Here, the beggar Xianglin’s wife is on left-hand side while the scholar is center stage with his face at the center of the panel: Does he not look a lot like Lu Xun? By means of this depiction of the scholar and by implying an identity of the fictional character with the original author of the story, the 1957 version manages to implicitly reintroduce the first-person narrator into the plot. After all, the confrontation with Xianglin’s wife’s questions and inquiries into afterlife as well as the discomfort he experiences faced with his own speechlessness were the reasons for discomfort for the narrator. Likely, such a depiction of what could be perceived as “Lu Xun” – in scholarly gown and in an ambivalent pose (after all, on the next page, we see Xianglin’s wife dead, implying the co-responsibility of the scholar in her death) might have been too much to risk in 1974 when Lu Xun had to fulfill his role as a revolutionary who contributed to the right cause with his pen unswervingly and without hesitation.

Page 56

The differences in historical framing among the two versions become more obvious in their respective forewords. While the 1957 version consists of a brief summary of the plot given in relative neutral terms (as we use a digital version of the 2005 reprint which carries both a foreword and a 1963 publication remark, we assume that this is also the 1957 text, though, we cannot be fully certain of this), the 1974 foreword is more elaborate: The plot summary is about twice as long, uses much stronger vocabulary to present the story in the rhetoric of the Cultural Revolution. A second page of the same length reinforces this, first, by framing the story (and the lianhuanhua) as a valuable contribution to the current campaign to criticize Lin Biao and Confucius, second, by pointing out how the suffering of Xianglin’s wife can be attributed to feudalism and the teachings of Confucius and Menzius and, third, by pointing out how Lu Xun intended to mobilize the “people to struggle against these cannibalistic forces” thus not only emphasizing the revolutionary nature of Lu Xun and his literature but also making use of the cannibalism trope.

On the one hand, the adaptations represent a reduction of the complexity and ambiguity of Lu Xun’s original and as such can be seen as a losing in the course of adaptation, with the realism inscribed into the images and with the loss of the ambiguous first-person narrator from Lu Xun’s short story. On the other hand, however, the comics in their variety of framing and individual painting styles serve to keep the story visible and meaningful to later generations of readers. In their simplicity, they provide access to the story to a readership who may not be literate enough to read the original – and they may add a distinct interpretation of the story for those readers familiar with the original, thus clearly representing a gain in adaptation.

References #

Denton, Kirk, A. 2016: “Literature and Politics: Mao Zedong’s ‘Yan’an Talks’ and Party Rectification”, in: Kirk A. Denton [ed.]: The Columbia Companion to Modern Chinese Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, 224-230.

Henningsen, Lena 2021: Cultural Revolution Manuscripts: Unofficial Entertainment Fiction from 1970s China, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hoffmann, Hans Peter 2015: „Der Neujahrssegen Lu Xuns – Ein Essay zum literarischen Übersetzen", in Lu, Xun 2015 (1924): Der Neujahrssegen (transl. Alisa Daniczek, Brigitte Höhenrieder, Hans Peter Hoffmann, Julia Neubauer, Angelika Opitz; edition pengkun), Bochum: Projektverlag, 43-72.

Lu Xun 鲁迅 2005 (1963, 1957): The New Year’s Sacrifice 祝福, adapted by Xu Gan 徐淦, illustrated by Yong Xiang 永祥, Hong Ren 洪仁, Yao Qiao 姚巧, Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe. Accessed online at: https://www.sohu.com/a/355550011_120441479 (last access Jan. 28, 2022).

Lu Xun 鲁迅 1974: The New Year’s Sacrifice 祝福, illustrated by Yong Xiang 永祥, Hong Ren 洪仁, Yao Qiao 姚巧, Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe.

Lu Xun 鲁迅 1979: Xianglin’s Wife 祥林嫂, adapted by Wu Chen 吴琛, Mo Xin 沫, IMAGES Sun Weide 孙为德, Wang Qia 王恰, Shanghai: Renmin meishu chubanshe. (photos / movie stills)

Lu, Xun 2009 (1924): “New Year’s Sacrifice” (transl. Julia Lovell), in: Lu Xun: The Real Story of Ah-Q and other Tales of China: The Complete Fiction of Lu Xun, London: Penguin, 161-177.

Lu, Xun 2015 (1924): Der Neujahrssegen (transl. Alisa Daniczek, Brigitte Höhenrieder, Hans Peter Hoffmann, Julia Neubauer, Angelika Opitz; edition pengkun), Bochum: Projektverlag.

McDougall, Bonnie [ed.] 1980: Mao Zedong's “Talks at the Yan'an Conference on literature and art”, Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan.

About the translation #

In preparing this translation, our aim was to produce a text that would do justice to the legacy of Lu Xun, but more so, to the language and contents of the PRC adaptation of the story. In his essay accompanying his retranslation of the original short story into German, Hans Peter Hoffmann (2015) makes a convincing argument for the use of slightly outdated terms as markers for what Lu Xun wanted to emphasize as backward in his times. As we translated from an adaptation of Lu Xun’s story in rather blunt PRC language, we measure our translation against that language. We thus aimed at staying close both to the literal meaning of the text and to its spirit – bearing in mind that this is, likely, a story targeting not only adults, but also children; we also aimed at a translation that would not make the text longer than in the original, thus subverting the simplicity, elegance and brevity of lianhuanhua language. While many names in the Chinese language are ‘speaking names’ and thus reveal information about the person or place they relate to, we opted for the more neutral terms derived at by transliterating and not translating the names in order not to unduly exoticize the translation. We also decided against adding explanations for terms into the text. But as the names of the protagonists and places may be confusing for readers unfamiliar with Chinese naming conventions, the following may be helpful:

Xianglin’s wife 祥林嫂: The protagonist of the story does not have a name of her own; much as she does not have any choice in her life, she is given a name and identity reducing her to being the wife of her first deceased husband which also seals the rest of her fate.

Luzhen 鲁镇: The name of the town – Luzhen – signals that it is a small town. The character for “Lu” in Luzhen is the same character as in Mr. Lu, the name of the uncle who the nameless narrator of the story has to stay with and whom he dislikes for his backwardness. This suggests that the Lu-Family is (and has been for generations) a central authority in town. It likely is not a coincidence that “Lu” both in “Luzhen” and in Mr. Lu is the same as in the penname the author of this story chose for himself: Lu Xun. While this by no means is an argument to declare that the first-person narrator represents or is Lu Xun himself, it is a signal of the text to play with autobiographical suggestions and hints.

Mr. and Mrs. Lu: Throughout the lianhuanhua, different variations are used for these two persons. For reasons of clarity, we are using Mr. and Mrs. Lu throughout. One recurring name is Lu Si Laoye 鲁四老爷 which might be translated as Old Master Lu Si or as Fourth Master Lu, thus emphasizing the reverence that townspeople would approach him with. There are also different terms used to address his wife. However, as her social status and all her comportment are defined by her being the wife of Mr. Lu, she is referred to as Mrs. Lu throughout the translation.

Auntie Liu 柳妈: Her name would have been literally translated as Mother Liu. We settled on Auntie Liu wishing to emphasize that she is a – likely unmarried – poor woman in town helping out with the Lu family. Auntie here does not signal a kinship relationship, but is more used as a form of address.

Old Wei: Likewise, the matchmaker is a – likely unmarried – woman in town.

Hejia Village 贺家墺 (Hejia’ao) and He Laoliu 贺老六: Similar to the Lu family and Luzhen, there is a relationship between Hejia Village and Xianglin’s wife’s second husband: The name of the village could literally be translated as He-Family-Village suggesting that it is predominantly inhabited by the He clan. He Laoliu’s name literally means He Old-Six, likely indicating him to be the sixth son, or, more likely the sixth male offspring in his generation thus taking into the account also his male cousins.

“The New Year’s Sacrifice” 祝福: The title of the story is conventionally translated as “The New Year’s Sacrifice” or “New Year’s Sacrifice”. In the aforementioned essay, Hans Peter Hoffmann makes a convincing argument to translate the title as “The Blessing” (German: “Der Neujahrssegen”), as this captures much more succinctly the contrast between the blessing that the well-to-do families receive and the misery that Xianglin’s wife experiences (2015: 47-52). “The New Year’s Sacrifice” sets the focus on Xianglin’s wife and her being a victim of ‘old feudal society’ which literally sacrifices her life in order to hold on to customs that place dead ancestors above those living and suffering today. The more literal translation “The Blessing”, Hoffmann points out, is both closer to the actual meaning of the word and refocuses and complicates the narrative. It emphasizes that through the ritual those who perform it receive a blessing, or benediction. In that way, it emphasizes old customs prevalent in the town. As a consequence, the individuals in Luzhen, including the nameless narrator, attain more agency and personal responsibility for what is taking place. As this particular adaptation of the story emphasizes – as do the translations of the story which are entitled “The New Year’s Sacrifice” – the sacrificing of Xianglin’s wife, we have decided to opt for this translation as well.

We have taken much effort to contact the publisher of this comic in order to acquire permission by the copyright holder to publish the pages online. We regret that we have not received responses to our inquiries. If you believe that copyrights are not being respected, please send us an email message. We will respond as soon as possible and will work with you to either accredit the material correctly or remove it entirely.

Read the translated lianhuanhua #

- Front and back cover

- Frontmatter 01

- Frontmatter 02

- Frontmatter 03

- Page 01

- Page 02

- Page 03

- Page 04

- Page 05

- Page 06

- Page 07

- Page 08

- Page 09

- Page 10

- Page 11

- Page 12

- Page 13

- Page 14

- Page 15

- Page 16

- Page 17

- Page 18

- Page 19

- Page 20

- Page 21

- Page 22

- Page 23

- Page 24

- Page 25

- Page 26

- Page 27

- Page 28

- Page 29

- Page 30

- Page 31

- Page 32

- Page 33

- Page 34

- Page 35

- Page 36

- Page 37

- Page 38

- Page 39

- Page 40

- Page 41

- Page 42

- Page 43

- Page 44

- Page 45

- Page 46

- Page 47

- Page 48

- Page 49

- Page 50

- Page 51

- Page 52

- Page 53

- Page 54

- Page 55

- Page 56

- Page 57

This translation was produced in a joint translation project by students at the Institute of Chinese Studies, University of Freiburg, supervised by Lena Henningsen. We acknowledge the support of the ERC-funded project “The Politics of Reading in the People’s Republic of China” (READCHINA, Grant agreement No. 757365/SH5: 2018-2023). Special thanks go to Eve Y. Lin for her critical reading of the translation and to Matthias Arnold and Hanno Lecher from the Centre for Asian and Transcultural Studies (CATS), Heidelberg University, for providing us with high resolution scans of the comics which are part of the Seifert collection. ↩︎

This essay has been developed as part of the project “The Politics of Reading in the People’s Republic of China” (READCHINA) which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 757365) and as part of the class “Comics in China” (winter 2021/2022) taught at the University of Freiburg. ↩︎