Lianhuanhua Adaptations of Life of Norman Bethune 白求恩的故事连环画改编两则 (1973, 1979) #

Norman Bethune 白求恩, edited by Wu Wenhuan 吴文焕, drawn by Hu Kewen 胡克文, Sheng Liangxian 盛亮贤, and Zhou Yunda 周允达, translated by Lena Henningsen and Ayiguzaili Aboduaini, Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe, 1973.1

Doctor Bethune 白求恩大夫, provided by Shanghai Film Studio 上海电影制片厂, adapted by Wu Wenhuan 吴文焕, translated by Lena Henningsen and Ayiguzaili Aboduaini, Shanghai: Shanghai renmin meishu chubanshe, 1979.1

translation and introduction: 15 January 2026

Introduction to the Lianhuanhua on Norman Bethune #

Lena Henningsen and Ayiguzaili Aboduaini

Surgeon, Comrade, Martyr and Icon – Who was Norman Bethune? #

Norman Bethune was a Canadian surgeon and member of the Canadian Communist Party. In this dual role, he joined the communist forces in their fight against the Japanese invaders in the spring of 1938 treating wounded soldiers and improving the conditions of medical care at the frontlines. Only one and a half years later, he died of a blood infection contracted during his work as a surgeon. His medical efforts, selflessness and heroism are familiar to many in China as they have been retold across various media, including a movie and the two lianhuanhua adaptations translated here. Bethune is, in fact, a household name throughout China as Mao Zedong composed a brief commemorative essay about the Canadian doctor soon after the latter’s death: “In Memory of Norman Bethune” 纪念白求恩 (21.12.1939). This essay would later become one of the “three old essays” 老三篇, together with “The Foolish Old Man who Removed the Mountains” 愚公移山 and “Serve the People” 为人民服务. These three short pieces would become compulsory reading, in particular during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, illustrating a few core concepts of Chinese communism. As a side effect, the story of the Canadian doctor celebrated for his selflessness, also become widely known.

In Memory of Norman Bethune #

Mao’s essay, which can be read in English here, consists of four paragraphs. In the first, Mao describes Bethune’s work at the frontline, asking: “What kind of spirit is this that makes a foreigner selflessly adopt the cause of the Chinese people’s liberation as his own?” The answer is twofold: it is, firstly, the spirit of internationalism, in line with the teaching of Leninism, acting beyond the confines of “narrow nationalism and narrow patriotism”. The second – Mao elaborates in the second paragraph – is selflessness and responsibility towards patients and people. Everyone who ever met Bethune was full of praise, and so Mao calls upon his readers that “[e]very communist must learn this true communist spirit from Comrade Bethune.” In the brief third paragraph, Mao sets Bethune’s medical skills as a model for everyone to strive for technical skills themselves. In the last paragraph, Mao briefly describes his own relationship to the Canadian, regretting that they only met once and that he only responded to one of the many letters Bethune wrote to him, and expressing his grief at the death of Bethune. Yet, the spirit of Norman Bethune survives and should be a model to everyone: “We must all learn the spirit of absolute selflessness from him. With this spirit everyone can be very useful to the people. A man’s ability may be great or small, but if he has this spirit, he is already noble-minded and pure, a man of moral integrity and above vulgar interests, a man who is of value to the people.”

Bethune as part of the Maoverse and Remediation into two Lianhuanhua #

Bethune’s legacy rests on his deeds, but also on a number of historical documents, including his own writings and photographs of him, such as those taken by the Michael Lindsay or the photo-journalist Sha Fei (沙飞 1912-1950, born as Situ Chuan 司徒传 and also renown for taking the last photographs of the famous author Lu Xun), available through the Historical Photographs of China collection:

Dr. Norman Bethune operating on an injured soldier in the Songyankou model ward, Wutai

Source: photograph by Sha Fei. Image courtesy of Michael Lindsay Special Collections, University of Bristol Library.

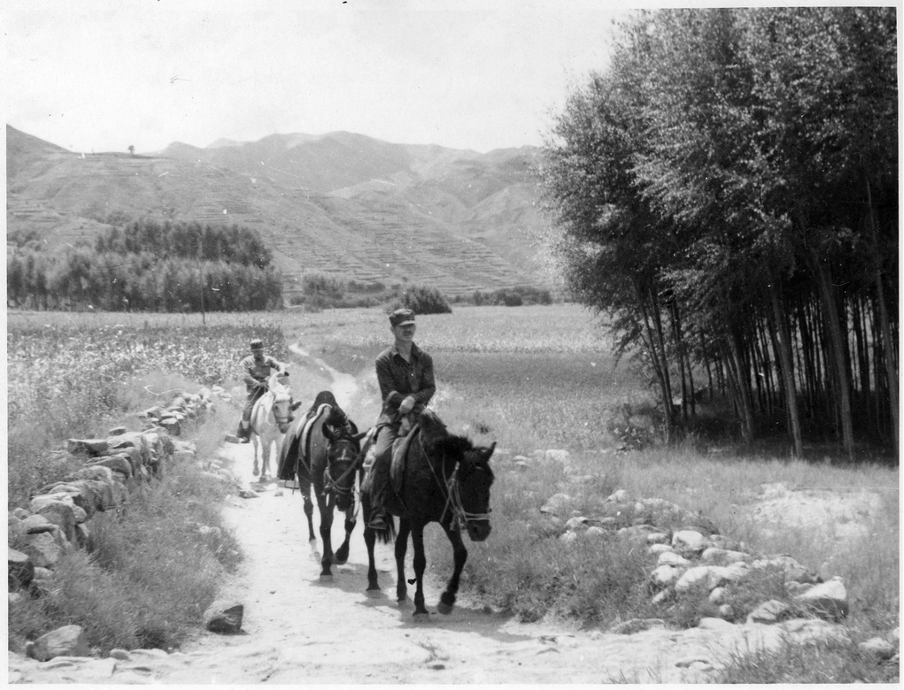

Dr. Norman Bethune on horseback, travelling from the hospital to military headquarters

Source: photograph by Michael Lindsay. Image courtesy of Michael Lindsay Special Collections, University of Bristol Library.

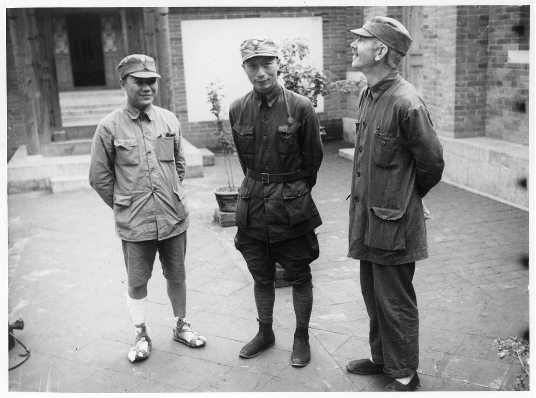

Dr. Norman Bethune’s interpreter (Dong Yueqian), General Nie Rongzhen (Nieh Jung-chen 聂荣臻), and Dr. Norman Bethune, 1938

Source: photograph by Michael Lindsay. Image courtesy of Michael Lindsay Special Collections, University of Bristol Library.

The relationship between Bethune and Mao is, in many respects, a textual one, and it is a relationship of transmediation. The story of Norman Bethune in China in itself is a story of remediation: from a real-life person, to propaganda object, first as the topic of one of the “three old pieces”, and then a multitude of follow-up items, including posters, movie and lianhuanhua. More than that, he also appears as a source of inspiration across other stories, for example in the Diary of Lei Feng and some of its lianhuanhua adaptations or in the many lianhuanhua narrating stories of the barefoot doctors who describe themselves as inspired by the Canadian doctor. One of lianhuanhua translated here, Doctor Bethune 白求恩大夫, even is a twofold remediation of the biography of Bethune: a 1979 adaptation of the 1965 year award-wining movie with film stills alongside captions. It is a prime example of what Nick Stember has termed “paper cinema”. The other one, Norman Bethune白求恩, was first published in September 1973 during the waning years of the Cultural Revolution. Through Mao’s essay and its massive popularization, Bethune and his story became well-known throughout China. He became remediated into posters, and movie adaptation, thus joining a pantheon of revolutionary heroes and martyrs who the people were and are called upon to emulate: Lei Feng, Huang Jiguang, Liu Hulan, Dong Cunrui to name but a few, as well as Mao Zedong, the radiating sun that is at the core person within this universe of superheroes, the Maoverse. The posters featuring Bethune, as sampled in the Landsberger collection foreground three aspects: his dedicated medical work, his relationship to Mao and his legacy. The first, medical work, is depicted with Bethune at an operation table or attending to patients. The second, his relationship to Mao, is rendered when he is depicted along excerpts from the famous essay – i.e. a textual remediation – and when he is depicted in conversation with Mao during their one and only in person meeting. The third, his legacy, is illustrated with other figures, such as barefoot doctors, taking Bethune as their model. Interestingly, the posters thus depict a core event – the meeting of Mao and Bethune – that both lianhuanhua translated here chose not to illustrate (a third lianhuanhua, the 1973 prize winning Norman Bethune in China 白求恩在中国 does depict the event). While this may be seen as a weakening the effect of the lianhuanhua – why not portray Bethune together with Mao, the center of the Maoverse? – it actually serves to highlight his importance as the center of the Maoverse through visual absence. In Norman Bethune, the meeting of Bethune and Mao is rendered through the eyes of the onlooker, waiting outside thus giving the meeting an aura of the sacred (panel 14). Yet Mao is ever present, albeit textually: sending or receiving messages; and through his own works that Bethune studies assiduously or that are quoted throughout; in Norman Bethune, these quotations are rendered in bold print, as common for quotations of Mao during the era of High Maoism, and the reader is provided with the titles Bethune read: “On Protected War” and “Problems of Strategy in Guerilla War Against Japan” (panel 46).

The two lianhuanhua translated here are but a few of the lianhuanhua covering the life of the Canadian doctor. Judging from publication data, there are at least eleven different lianhuanhua created by different artists and published by different publishers between 1950 and 1983 (from publication data alone, it can be difficult to be totally sure whether a lianhuanhua with the same title (most of them are entitled Bai Qiu’en 白求恩) naming a different artists is indeed a unique publication, so we are cautious in our estimate. There are, however, at least 25 uniquely listed lianhuanhua about Bethune, two of them in two volumes. Three of the lianhuanhua were created from the movie pointing to the large ideological and commercial potential attributed to it. Some of the lianhuanhua were subsequently also published in languages other than Mandarin, including Kasak, Mongolian, Korean, Uighur, and Tibetan (some of them in bilingual editions pointing to the dual educational purpose of these booklets as language and political education, Zhang et al 2003). As such the lianhuanhua had a long-durée impact with multiple reprints across the decades as well as distinct impact one at specific points of time, with Norman Bethune reaching a print run of 750.000 already in its second printing in October 1973. The widest reach, likely, had an adaptation not (yet) covered in our collection: Norman Bethune in China 白求恩在中国 by Zhong Zhicheng 钟志诚 (text) and Xu Rongchu 许荣初, Xu Yong 许勇, Gu Liantang 顾莲塘 and Wang Yisheng 王义胜 (illustrations) was first published by Liaoning renmin chubanshe in September 1973, i.e. at the exact same time as Norman Bethune. It saw at least eight (probably ten) later editions, including three (probably five) into other languages between November 1976 and January 1978. The 1975 edition by Renmin meishu chubanshe had almost a million copies printed, flooding the second-hand book market until today.

A few remarks on the editions used, on concrete terms and items in the texts and on our translation choices #

On Norman Bethune 白求恩 (1973) #

Like many lianhuanhua, Bai Qiu’en (Norman Bethune) saw several editions and reprints. For this translation, we have consulted two editions, both available in the Andreas Seifert Collection at Heidelberg University: published by Shanghai People’s Publishing House in 1973 and by Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House in 2005 respectively. Yet, these two differ as to the contexts in which they were published. As mentioned above, the 1973 version was printed in high numbers (reaching 750.000 a month after first publication) catering to a large readership during the time of High Maoism, whereas the 2005 version was printed in only 4000 copies. The textual and aesthetic choices demonstrate how the same work was published in different historical contexts.

A close examination of both editions reveals several key findings regarding their artistic continuity and technical evolution. The text scripts in each version were authored by Wu Wenhuan, and both faithfully preserve the original illustrations without modification, ensuring complete visual consistency and authenticity. However, while the 1973 edition credits three artists (Hu Kewen, Sheng Liangxian, and Zhou Yunda) as illustrators, the 2005 version only acknowledges Hu and Sheng, omitting Zhou Yunda’s contribution despite maintaining all original artwork intact.

The text is also identical in both editions, but printed in different directions. The 1973 edition employs horizontal typesetting, reflecting China’s modernization push during its script reform era, while the 2005 edition purposefully returned to traditional vertical typesetting, a shift embodying the cultural heritage revival of post-1990s China, mirrored across a number of lianhuanhua, in particular in classic republications like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.

The 2005 edition features significant supplementary content that enhances its value as a scholarly and artistic resource. It begins with a contemplative preface titled “Reflections on the Cultural Charme of Lianhuanhua” (连环画文化魅力的断想) authored by the publishing house director, which serves as a substitute foreword analyzing the art form’s cultural significance. Notably, it includes a handwritten “Artist’s Statement” (画家自述) by illustrator Hu Kewen, detailing the creative process and contextual background of the artwork. The appendix further enriches the publication with comprehensive biographical profiles of both Hu Kewen and Sheng Liangxian, accompanied by chronologically organized lists of their major works, documenting their artistic evolution. Concluding the volume is a publisher’s formal call for submissions, inviting new contributions to perpetuate the tradition of lianhuanhua.

For our translation of the quotation from Mao’s “In Memory of Norman Bethune” in the paratext, we have consulted the translation provided by Marxist.org, but have rendered the text slightly different as we feel this is more precise. Also, for better readability, we use the term “comrade” both for the Chinese tongzhi 同志 and, in a few cases, for zhanyou 战友, aware of the slight differences among the two terms: Tongzhi designates a fellow communist, whereas zhanyou refers to a fellow soldier, or comrade-in-arms.

The beginning of the lianhuanhua narrates Bethune’s life prior to his arrival in China. Panel 5 relates his earlier efforts, in 1936, leading a medical team in the Spanish civil war against the fascists. We remained faithful to the original in our translation that “the fascist regimes of Germany and Italy invaded Spain”, Bethune led a medical team to Madrid, the capital of Spain, even though this is factually wrong as Nazi Germany supported the Franco regime, but did not invade the country.

Whereas the captions to the lianhuanhua are given in simplified Chinese characters, the slogans painted on one of the walls in the village are: “Fight Japanese imperialism!”, “Long live the people’s revolutionary struggle!”, “Long live the Chinese Communist Party!” (panels 24 and 79). The slogans, albeit merely in the background to the action in the village, underline the people’s support of the CCP and, by implication, the PLA. The fact that these characters are drawn in not simplified form underpins their historicity – Bethune’s stint in China in the 1930s was long before the character reforms undertaken after the founding of the PRC.

On Doctor Bethune 白求恩大夫 (1979) #

A few notes on the translation #

Our aim in this translation – as in other translations – was to remain faithful to the original, yet produce a readily accessible translation. Some terms, and of our translation choices may warrant brief explanations.

The song (gequ 歌曲) that is sung at the beginning of the story is “Song of the Guerrillas” (panel 1), composed by He Luting (贺绿汀, 1903-1999) in 1937. It was first sung by the “Shanghai Cultural Circles Anti-Japanese and National Salvation Drama Troupe” during the Eighth Route Army Cadre Conference on January 6, 1938 under the direction of the composer and was later used as the theme song for the film Doctor Bethune, recurring later in the plot (panels 99 and 162).

Also, the first panel firmly locates the action into the heartland of the Chinese communist revolution with the “majestic Pagoda Mountain” bathed in “golden sunlight”. The pagoda is located in Baota District of Yan’an City, in Shaanxi Province to where the CCP had retreated after their legendary Long March.

As much of the story is taking place in Northern China and into the cold season, we see indoors scenes taking place with people sitting, or lying, on the kang 炕 – a brick structure traditionally built into Chinese in Northern China, heated from below to allow for warmth indoors (panel 118).

The lianhuanhua refers to the “famous battle of Huangtuling” (panel 143). The captions to the illustration wrongly refer to it as Huangshiling (士 instead of 土) which we have not corrected in the transcription, but in our translation. The battle took place in November of 1939 resulting in – as we learn from the lianhuanhua – a victory of the PLA forces. It can be assumed, however, that its fame rests not only on the bravery of the soldiers and the outcome of the battle, but on the fact that Mao Zedong explicitly refers to it in his equally famous essay “In Memory of Norman Bethune”.

Names #

Some of the names, and our choices for (non)translation deserve explanations. We transcribe given names into the pinyin transcription that is now standard in the PRC and in many foreign publications. Only for Chiang Kai-shek – then adversary of Mao Zedong and the communists – we use a different transcription form as this is how he is commonly known.

Norman Bethune #

The name of the protagonist – Norman Bethune – is rendered differently throughout the text. These different terms attribute both the speaker and the person addressed – the Canadian doctor – with different connotations: In the captions, he is typically referred to as Bai Qiu’en 白求恩, the official phonetic transcription of his name which captures the Canadian name in form identical to a “proper” Chinese name, with Bai (White) as a regular Chinese family name and Qiu’en as a potential given name. It is a given name with a poetic and fitting meaning: “Seeking Grace”. Bai Qiu’en is also the transliteration that Mao uses in his famous essay on Norman Bethune, though Mao in most cases adds the markers “comrade” (tongzhi 同志) or “doctor” (yisheng 医生). We translate Bai Qiu’en as Bethune. Others, usually the local rural people, address him as “Doctor Bai” (Bai Daifu 白大夫), or they refer to him as the “foreign doctor” (yang daifu 洋大夫) as he first arrives to the village (panel 5). Daifu 大夫, here, is a polite form of addressing Bethune that at the same time also signals respect and closeness. It also carries a clear colloquial and regional note, as it continues to be used in local dialects in Northern China. When Bai Daifu is used in the narrative passages, we render it as Bethune. The title of the lianhuanhua represents yet another variation on the term daifu: Doctor Bethune (Bai Qiu’en Daifu) 白求恩大夫. The other common Chinese term for doctor, yisheng 医生, is also translated as “doctor” throughout. Other than daifu, yisheng is less colloquial and more a professional denomination than a form of address – it is used as a denominator for Norman Bethune in the summary to the lianhuanhua (内容提要) where he is first named: “Comrade Norman Bethune, a Canadian Communist Party member and renowned surgeon” (白求恩同志,加拿大共产党员,著名外科医生), here, he is given with his full field of specialization (wailiao yisheng 外科医生). In the reminder of the text, the term yisheng is used for the Chinese medical staff amid the team and in questions as to whether or not they are sufficiently trained in the profession. We therefore translate these as “Dr.” in cases when yisheng is used to address a person: Dr. Wang, Dr. Fang or Dr. Ling (see panels 27, 34, 66 and 68). These dialogues elucidate the hardships the characters suffered, their high moral stance, and their willingness to go to great lengths to learn and then become dedicated doctors themselves.

Xiaohu and Er Niu, Xiao Shao #

Some of the characters have names that have a meaning: The little boy, for example, who first greets Bethune at his arrival to the village is called by his nickname “Xiaohu” 小虎 which could also be translated as “Little Tiger”, a common name given to young boys (see also our translation of Little Smarty Travels to the Future). In order not to exoticize his name too much, however, we have decided not to translate his name, but to only transcribe it. Likewise, his sister is called “Er Niu” 二妞, with Er being the number two and Niu referring to a young girl – so Er Niu might be translated as “Second Daughter”. Xiao Shao 小邵, similarly, could be rendered as “Little Shao”, with the xiao 小 / little denominator referencing a younger person, and Shao the surname. As it commonly functions like a name in everyday usage, we likewise do not translate the xiao here. (And likewise for Xiao Ma and Xiao Jia). Similarly, a few persons are addressed with the attribute lao 老 / old as an expression of their seniority. We likewise do not translate this form of address, but call the respective persons Lao Zhang 老张 (the elderly cook), Lao Jiang 老姜 (the older of two young men) and Lao Feng 老冯, with the latter clearly an honorable form of address more than a biological marker as “Old Feng” is a young female doctor highly esteemed because of her medical skills.

“Devils” #

The action takes place among fighting between the People’s Liberation Army and the Japanese troops. In line with linguistic practices in China under Mao (and beyond), the PLA’s enemy, the Japanese invadors, are referred to as “devil soldiers” (guizi bingjia 鬼子兵家, panel 56; or guizibing 鬼子兵 or only guizi 鬼子, p.e. panel 86; or guizijun 鬼子军, “devil army” panel 87) “. For better readability, we have not always rendered the devil in the translation, but refer to them as “Japanese”. Their dogs, likewise, are attributed devilish qualities: guizi liequan 鬼子猎犬, literally, devil’s or devilish hunting dogs which we render as “the enemy’s hunting dogs” (panel 88).

Conversely, Xiao Shao, the yound soldier assigned to assist Bethune in all practical matters, introduces himself “Doctor Bai, reporting to you, I am the little devil assigned to look after you” (panel 12). Bethune has no clue as to what this term means – until the very end of the story when he himself addresses Xiao Shao as “Little Devil”.

Place names #

Quhuisi Village (曲回寺村) literally translates as the “Village by the Quhui Temple” (panel 71).

During the war time, the capital of China had been moved to Nanjing (南京, literally translatable as “Southern Capital”) so that Beijing (北京, literally translatable as “Northern Capital”) was renamed Beiping (北平, literally translatable as “Northern Peace”, panels 131 and 166).

References #

Mao Zedong 1939: “In Memory of Norman Bethune”, translated by Marxist.org, https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mao/selected-works/volume-2/mswv2_25.htm.

Zhang Qiming 张奇明, Wang Yuxing 王玉兴 2003: Index of Chinese Lianhuanhua 1949-1994 中国连环画目录汇编 1949-1994, Shanghai: Shanghai huabao chubanshe.

Read the translated lianhuanhua #

This translation was produced by Ayiguzaili Aboduaini and Lena Henningsen. We acknowledge the support of the ERC-funded project “Comics Culture in the People’s Republic of China” (CHINACOMX, Grant agreement ID: 101088049). We thank our colleagues Matthias Arnold and Hanno Lecher from the Centre for Asian and Transcultural Studies (CATS), Heidelberg University, for providing us with high resolution scans of the comics which are part of the Seifert collection. ↩︎ ↩︎